In Defense of María Corina Machado—and Freedom Fighters Everywhere

Uriel Epshtein responds to María Corina Machado's critics. Jay Nordlinger contextualizes the award for the Venezuelan dissident and its place in Nobel history.

A note from Garry Kasparov: Last week ended on a high note. I won a rematch against my friend and fellow World Chess Champion Vishy Anand, thirty years to the day after we dueled atop the World Trade Center in New York. More importantly, RDI Hero of Democracy María Corina Machado was named this year’s Nobel Peace Prize laureate for her work defending freedom in Venezuela. María is one of the bravest people I know, and this honor is well deserved.

For some strategic insight into what Machado’s win means, we have two pieces in The Next Move from my Renew Democracy Initiative colleagues. Uriel Epshtein responds to Machado’s critics by putting the morally-complicated decisions dissidents have to make into context. Jay Nordlinger, who quite literally wrote the book on the Nobel Peace Prize, explains how the award often functions as a “freedom prize.”

Finally, because we don’t have enough good news—I want to celebrate these wins. To that end, we’ll have a special surprise coming at the end of the week. Stay tuned!

— Garry Kasparov

In Defense of María Corina Machado

By Uriel Epshtein

Uriel Epshtein is the CEO of the Renew Democracy Initiative.

By the way that some people reacted to last week’s Nobel Peace Prize announcement, you would’ve thought Donald Trump had received the award.

In fact, this is the argument that the left-wing magazine Salon made—that the person whom the Nobel committee ultimately chose, my friend and brave Venezuelan dissident Maria Corina Machado—is merely a proxy for Trump.

Salon’s executive editor, Andrew O’Heir writes:

[Machado] has repeatedly made clear that she supports US sanctions against Venezuela (as the government propaganda billboard illustrating this article alleges) and would favor a military coup or outside military intervention.

He then hits upon a critique I’ve seen echoed even among some of our subscribers:

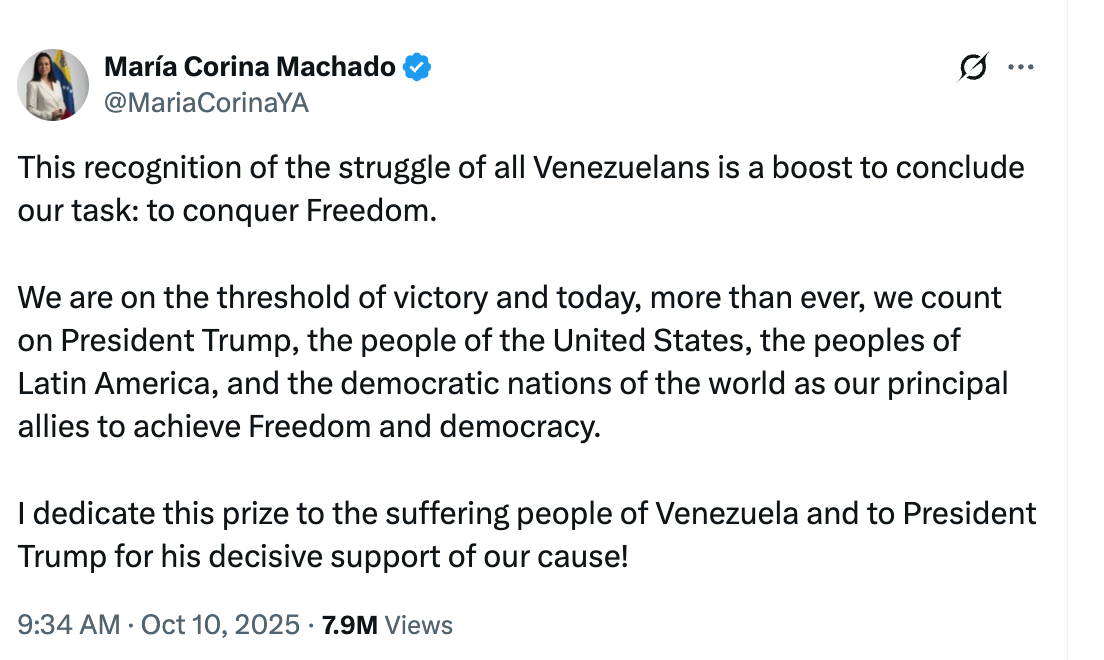

She abased herself before Trump as vigorously as she could after the Nobel announcement, even “dedicating” the prize to him, in an English-language tweet, “for his decisive support of our cause.”

Machado thanked Trump. How dare she?

With respect, what do these people think the job of a political dissident is under a dictatorship?

If a peaceful transfer of power were possible in Venezuela, this would be the dissident’s first resort. Don’t forget that Machado tried to run for president and was disqualified. When she and her colleagues were able to verify that Edmundo Gonzalez, the former diplomat who replaced her on the ticket, had won, the regime simply fudged the results and amped up the repression. The government murdered two dozen people in protests surrounding the election.

As far as tactics are concerned: of course she supports US intervention against dictator Nicolas Maduro. Should Machado, and those like her in Russia, China, Belarus, Nicaragua, and elsewhere stick to politely picketing outside of government offices when even that sort of mild-mannered protest can get you disappeared?

When The Next Move’s publisher, Renew Democracy Initiative, honored Machado this past April, she had to leave us a message by video with her daughter, Ana Corina Sosa representing her in person (Ana’s speech, by the way, was awesome. You should go watch it).

Next, let’s address that dedication to Trump. This one really riled people up.

Here’s Machado’s tweet:

First, there’s an awkward fact those of us alarmed by Trump’s efforts to centralize power need to reckon with: Trump has a problem with a grand total of three dictatorships. Venezuelans are lucky that theirs is one of them. If you’re curious, the other two are the Islamic Republic of Iran and Cuba.

From a Venezuelan point of view, Trump might appear better than another president. Certainly better than Joe Biden, who lifted sanctions against the Maduro regime. Yet, Machado is no partisan, and her political partner Edmundo Gonzalez happily met with Biden in Washington during the last administration.

Next, there’s the tactical. We all know that Trump was gunning for the Nobel himself with an unprecedented campaign. And we know that, given the president’s temperament, the fallout from him not getting the award could be, well, yuge. Indeed, all of Norway seemed to be on edge over the possibility that Trump might (erroneously) target the Scandinavian country’s government over snub despite Oslo playing no role in the awards process.

Trump’s frustration is not something Machado—whose people face a life-and-death showdown with a dictator—can afford to deal with. Dedicating the prize to him was an inelegant way out of an inelegant situation.

Consider Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s situation. After his showdown in the Oval Office with Trump and JD Vance, the Ukrainian leader changed tack. He is now more deferential, going for flattery over fight. When Zelenskyy arrives at the White House this Friday, I am sure that he will be full of praise for the president. Is it unfortunate that matters of geopolitical importance are decided by how well world leaders flatter the president? Yes. But Zelenskyy would be irresponsible if he didn’t pull every lever to get aid for his embattled nation.

That’s a simple fact many people fail to recognize.

Look at the top reply, from an anti-Trump account, under Machado’s dedication of the Nobel:

I don’t understand.

You received the Nobel Peace Prize for your efforts in building up democracy and fighting authoritarianism in Venezuela, yet, you offer praise to Donald Trump who is borderline doing the things Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro is doing.

How is that you fighting for democracy @MariaCorinaYA?

This person betrays an overwhelmingly America-centric worldview. Machado is a Venezuelan leader looking out for Venezuelan interests just as Zelenskyy is a Ukrainian leader looking out for Ukrainian interests. Their values are aligned with ours, and we are part of the same fight for freedom, but their tactics will differ with each of their individual struggles.

Self-styled pro-democracy activists in America might like the idea of dissidents in theory, but the moment those dissidents—often facing impossible choices—get their hands dirty, many turn away from them. Americans disappointed with Machado seem to expect that at a minimum she will ignore the most powerful man on the planet and, ideally, rebuke Trump outright and come out of hiding to our “No Kings” protests.

Get real.

Don’t blame Machado for thanking Trump or entertaining every option to win freedom for her country. It’s true that dissidents often tack to the right when transplanted into the American political context, especially if they come from communist or socialist countries. As the son of one such dissident, I can understand why this happens and believe we should take their concerns seriously. But their struggles for freedom—which are about fundamental human rights and free and fair elections—need not be a Republican issue. Once upon a time, this was one of the few areas where left and right could converge. We all supported doing what was necessary to liberate those seeking freedom.

It’s easy to moralize from behind the safety of our keyboards. Dissidents, however, don’t have the luxury of ideological purity. They have to navigate the cold realities of power and politics, not some utopian fantasy. So instead of making cheap jabs at dissidents like Machado while they navigate impossible circumstances, we ought to learn from these freedom fighters. We could use their wisdom—nowadays more than we’re probably comfortable admitting.

The Nobel Peace Prize as a Freedom Prize

By Jay Nordlinger

Jay Nordlinger is a senior resident fellow at the Renew Democracy Initiative and a contributor at The Next Move.

There are many inspiring freedom movements in the world, almost one for every dictatorship. One of the most inspiring of all is Venezuela’s. It includes many people and several leaders, including Leopoldo López, a former political prisoner now in exile.

(I interviewed López in 2021, and the resulting profile is here.)

In recent times, the opposition movement—the freedom movement, the democracy movement—has consolidated around María Corina Machado. She, like the other leaders, is an uncommonly brave person, whose life is under daily threat. She now lives in hiding.

Last week, the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced that it was awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to Machado. She is receiving the prize, said the committee, “for her tireless work promoting democratic rights for the people of Venezuela and for her struggle to achieve a just and peaceful transition from dictatorship to democracy.”

The committee also made a broader statement about democracy:

…we live in a world where democracy is in retreat, where more and more authoritarian regimes are challenging norms and resorting to violence. The Venezuelan regime’s rigid hold on power and its repression of the population are not unique in the world. We see the same trends globally: rule of law abused by those in control, free media silenced, critics imprisoned, and societies pushed towards authoritarian rule and militarisation. In 2024, more elections were held than ever before, but fewer and fewer are free and fair.

Earlier this year, we at the Renew Democracy Initiative made María Corina Machado one of our Heroes of Democracy. She spoke to our gala by video, and her daughter, Ana Corina Sosa, spoke to us in person. (To see and hear these speeches, go here.)

Sometimes, the Nobel Peace Prize is a freedom prize. I detail this in my history of the prize, Peace, They Say.

The first real “freedom prize,” out of Oslo, was that for 1960. This was a prize given for a freedom struggle in one country, rather than for peacemaking between nations.

The laureate was Albert John Lutuli, of South Africa. He was an extraordinary man: a Zulu chief; a Christian lay pastor; the president of the African National Congress.

In his acceptance speech, Lutuli made a characteristically graceful remark. He noted that the interior minister in South Africa had said that he, Lutuli, did not deserve the Nobel. “Such is the magic of a peace prize,” said Lutuli, “that it has even managed to produce an issue on which I agree with the government of South Africa.”

No one receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, said Lutuli, “can escape a feeling of inadequacy.”

In 1975, the committee gave the prize to a hero in the Soviet Union: Andrei Sakharov, the great physicist who had become a great human rights champion. On hearing that he had won the prize, Sakharov said, “I hope this will help political prisoners.” The Kremlin denounced him as an “anti-patriot,” an “enemy of détente,” and a “Judas for whom the Nobel prize was 30 pieces of silver from the West.”

The Kremlin, making a biblical analogy?

Sakharov was not permitted to leave the Soviet Union to go to Oslo and participate in the Nobel ceremony. But his wife, Yelena Bonner, was there, and she read the speech that Sakharov had prepared.

In this speech, he paused, essentially, to name the names of political prisoners: approximately 100 of them.

Years later, I interviewed Bonner, who said, “The listing of names brought joy to the prisoners of conscience, and to their relatives. More important, it somewhat protected them from the camp administration.”

She further said that “listing specific people, and caring about a particular person, as opposed to general arguments about human rights, fulfilled a most important inner need for Sakharov.”

In 1983, the Nobel committee gave its prize to Lech Wałęsa, the leader of the Solidarity movement in Poland. The movement had been banned by the dictatorship but was operating underground. In Washington, President Reagan said that the award to Wałęsa was “a triumph of moral force over brute force” and “a victory for those who seek to enlarge the human spirit over those who seek to crush it.”

Wałęsa did not travel to Oslo to pick up his prize. He thought that the dictatorship would not let him return home. Better, from their point of view, to have him out! His wife, Danuta, went to Oslo to represent him.

In a 2010 interview, Wałęsa told me that the prize had meant everything to the Solidarity movement. He put it this way: “There was no wind blowing into Poland’s sail. It’s hard to say what would have happened if I had not won the prize. The Nobel prize blew a strong wind into our sail.”

Has it now done the same to Venezuela’s?

Has it made a difference in Iran? In 2003, the laureate was Shirin Ebadi, an Iranian human rights lawyer. She told me that the prize did help, yes. For one thing, she said, it “demonstrated to the Iranian people that human rights are the best way of realizing democracy.” Plus, the prize amplified her voice. It handed her a potent megaphone.

Twenty years later, in 2023, the committee awarded an Iranian political prisoner, Narges Mohammadi, who had worked with Ebadi. She was not let out to go to Oslo. Her twin children, Ali and Kiana Rahmani, who live in exile, spoke in her stead.

Has the Nobel prize made it harder for the Iranian authorities to kill Mohammadi? Probably so.

May it do the same for Ales Bialiatski. He is a laureate for 2022, and he is a Belarusian political prisoner. His wife, Natallia Pinchuk, represented him in Oslo. He is a stupendously brave man.

So was Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese democracy leader. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, in absentia. He was a political prisoner. But he got word out that he was dedicating the prize to “the lost souls of the Fourth of June”—in other words, to the victims of the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989.

Liu Xiaobo died in 2017, still a political prisoner.

When the prize for María Corina Machado was announced last week, Jianli Yang had some notable words. He is a Chinese democracy leader and former political prisoner, long in exile. He wrote,

In many ways, Machado embodies the spirit of the late Nobel peace laureate Liu Xiaobo, whom I had the honor of representing at the Nobel ceremony on December 10, 2010. Liu warned that without individual moral courage and civic responsibility, even the best-intentioned reforms would collapse into new forms of tyranny. He urged intellectuals and ordinary citizens alike to resist hatred, to choose conscience over obedience, and to recognize that democracy cannot be bestowed from above—it must grow from the bottom up, through personal awakening and the practice of truth-telling.

I wonder: Will María Corina Machado, wherever she is, be able to attend the Nobel ceremony in Oslo on December 10, 2025? In a conversation with a Nobel official, she could only say that she hoped so.

Back in April, Machado said the following to the guests at the Renew Democracy Initiative gala: “The truth is that no dictator is so entrenched that he cannot be removed.”

The Venezuelan dictatorship has powerful backers: the dictatorships of Russia, China, Cuba, Iran, and so on. This is the same coalition, in fact, working on the annihilation and subjugation of Ukraine. There is a Free World. What will it—what will we—do?

On the fence about becoming a paid subscriber? We have a special offer to make the decision easier for you: $49 for an annual subscription—a 30% discount—now through November 8. Paid subscribers get exclusive benefits like access to interactive Zoom calls with Garry Kasparov.

More from The Next Move:

How Trump Got a Gaza Ceasefire

The very qualities that make Trump dangerous domestically made him uniquely capable of delivering a win in Gaza.

In expressing appreciation for support by Trump, Machado is in part following the example of the American Revolution. In that struggle against the king and parliament of Great Britain for a legislative voice in the levying of taxes and other features of representative government, Americans solicited military support from various govenments, including the corrupt monarchy of France. Advocates for democracy appealing to the world outside their borders often find that the enemy of their enemy can be a useful friend, even when that friend may not be a model for democracy.

You do what you need to do to accomplish your goal, and if flattering Trump is one of those , so be it. You do imperfect things to deal with an imperfect world. So much counterproductive nonsense generated by elements of the left.