Editor’s Note: Berlin Freedom Week kicked off with a conference on November 10. Yesterday, we published Part I of Jay Nordlinger’s journal. The journal concludes today.

Jay Nordlinger is a senior resident fellow at the Renew Democracy Initiative and a contributor at The Next Move.

For generations, political prisoners have been helped by family members, campaigning in exile. Sebastien Lai has certainly been doing his part for his heroic father, Jimmy Lai, imprisoned in Hong Kong.

And he speaks for his father here in Berlin. As I have said to Sebastien more than once: What a pleasure it would be, to shake the hand of Jimmy Lai—liberated. I hope to do so one day.

(For a podcast I did with Sebastien two years ago, go here. For a piece of mine on the life and times of Jimmy Lai, go here.)

***

Evgenia Kara-Murza campaigned for her husband, Vladimir Kara-Murza, when he was imprisoned in their native Russia. Carine and Anaïse Kanimba campaigned for their father, Paul Rusesabagina, when he was imprisoned in their native Rwanda.

The Kara-Murzas, and Rusesabagina and Carine, compose a panel of four here in Berlin.

Rusesabagina says, among other things, that Free World governments ought to do what they can, for imprisoned freedom advocates. I think of a statement by Alexander Solzhenitsyn:

On our crowded planet, there are no longer any “internal affairs.” The Communist leaders say, “Don’t interfere in our internal affairs. Let us strangle our citizens in peace and quiet.” But I tell you: Interfere more and more. Interfere as much as you can. We beg you to come and interfere.

Vladimir Kara-Murza explains that he was released from prison on August 1, 2024, in a swap that involved eight countries. Sixteen people came out of Russian custody and eight agents of the Kremlin were returned to Russia. Half of the 16 who came out of Russia were Western hostages, and the other half were Russian political prisoners.

Kara-Murza says,

Western countries have a legal duty to advocate for their own citizens. They did not have a legal duty to advocate for us, but they did, and by doing that, they sent the clearest and loudest possible message of solidarity and support for all those Russian citizens who are standing up against this criminal war in Ukraine and for freedom in Russia itself.

And this was the strongest possible recognition by Western democracies that the real criminals are those people who are sitting in the Kremlin—who are waging this war—and not those of us who have been imprisoned because we oppose it.

On average, says Kara-Murza, five people a day are arrested in Russia “on politically-motivated charges.” And there are more political prisoners in Russia today than there were in the whole of the Soviet Union during the last stage of the Cold War.

The USSR, Kara-Murza reminds us, comprised 15 present-day countries. And there are more political prisoners in Russia alone than there were in the USSR.

He is not content with speaking of political prisoners in the abstract. Oh, no. He names four of them, and says that if he kept going, “we would be here all day.”

The four he names are Alexei Gorinov, Maria Ponomarenko, Maxim Kruglov, and Arseny Turbin—who was arrested when he was only 15 and is today 17.

People such as these, says Kara-Murza, “could not look the other way.” They “have the courage to stand up against injustice and oppression, and the conscience to distinguish right from wrong, and the courage to say what they know to be true out loud.”

Kara-Murza recalls a statement by Tolstoy—or rather, a statement uttered by one of his characters, in his final novel, Resurrection: “Yes, the only place befitting an honest man in Russia at the present time is a prison.”

***

Taking the stage, for a musical interlude, is the children’s choir of the Berlin State Opera (a.k.a. the Staatsoper Unter den Linden). They sing a pop song—which I do not recognize—and then something by Beethoven: the tune from the last movement of his Ninth Symphony known as “Ode to Joy.”

A nice interlude indeed.

***

Masih Alinejad, the dissident from Iran, interviews two women from Afghanistan: Shukria Barakzai and Roya Mahboob. The former is a politician and journalist, the latter a businesswoman. They are both human rights defenders. And, of course, if they were in their native country today, they would be in prison, if they remained alive.

With Masih, the two Afghans talk about the fate of girls and women, in particular—the fate of girls and women in Afghanistan under the Taliban. It is a sorry, wretched fate.

Elsewhere in Berlin, I will meet a young man from Afghanistan. He is working as an Uber driver. He got out of Afghanistan and had a circuitous route to Germany—via Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, Greece, Hungary, Serbia, and Austria. There was drama at every turn, and there has been drama since.

“You should write a book,” I tell him. “I have!” he says. He did so while he was in prison (part of the drama).

He works hard and sends every cent he can back to his family in Afghanistan. He is consumed with worry about one person in particular: his 12-year-old sister. What will her future be? She is forbidden to go to school. “Some man with a beard, 40 or 50 years old, can come and take her as a slave,” he says. “No one will do anything about it.”

This man’s testimony is both powerful and typical. When we part, he says, earnestly, “Thank you for listening to me.”

***

For years, a plaint of many of us has been, “Dictatorships are really good at allying and cooperating. Why can’t democracies be half as good?” This is a theme sounded by Tsai Ing-wen, here at the Berlin Freedom Conference. From 2016 to 2024, she was the president of Taiwan. For the past three and a half years, there has been a remarkable degree of solidarity between Taiwan and Ukraine.

Russia’s full-scale invasion, says Tsai, was “a wake-up call for all.” She further says this: “Today, Taiwan is on the front lines of the defense of democracy. Tomorrow, it could be any one of us.” Democracies, she says, need to band together.

Things are connected “on our crowded planet,” to borrow Solzhenitsyn’s phrase. The indivisibility of freedom may be a cliché—but it has practical import as well.

***

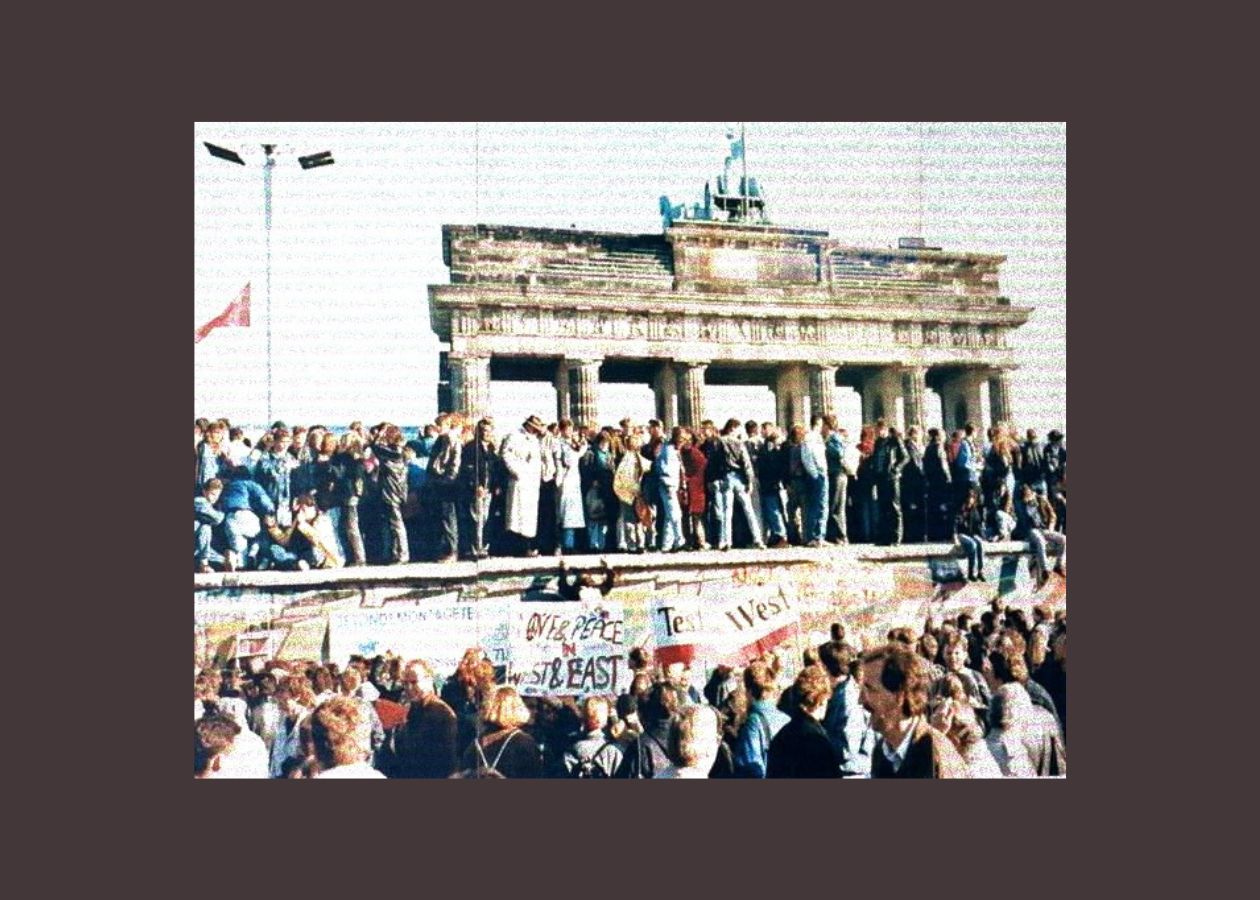

Berlin Freedom Week is a very good idea. I already look forward to next year. Maybe I could close this year’s journal by showing you a banner—a banner on the façade of a museum here in Berlin. The museum is dedicated to the Berlin Wall, which divided Europe—and, in a sense, divided the Free World from the Unfree World—for nearly 30 years.

More from The Next Move:

FOFCON Pod: When Garry Met Gorby

Garry Kasparov talks chess, America’s Putin apologists, and meeting the last Soviet leader.

To the Village Idiwitt, the only place befitting for anyone who has, or would hurt your dear friends in Berlin is prison…or a…forgive me Jesus, unlike Pope Francis a sissy I still believe in the ultimate punishment for monsters, I mean mobsters that would touch a hair on any of Jays friends…like so yesterday. Please God, deliver U.S. from the evil that is the psycho killer Trump (he only orders people whacked that can’t threaten his corrupt domain) administration and send all the monsters that hurt all these good peoples Jay writes about six thousand feet down under….Or , at the very least, can some so called leader in the still free Western World place a billion dollar bitcoin bounty on the Axis of Evil doers Dons Xi, Putin and Darth Vadar of Terroran Gotta run on. Thanks for taking my rant Onward and Upward. Peace through superior mental firepower

"Western countries have a legal duty to advocate for their own citizens.

They did not have a legal duty to advocate for us, but they did ..."

Will the U. S. of Authoritarianism, any longer?