Jay Nordlinger is a senior resident fellow at the Renew Democracy Initiative and a contributor at The Next Move.

One of the questions roiling our politics is, “What is conservatism?” That is a good question, for any period.

Time was, most Americans had a pretty good grasp on “conservative” and “liberal.” For instance, Ronald Reagan was conservative, and Walter Mondale was liberal.

But those terms are increasingly slippery. These days, when people say “conservative” or “liberal” to me, I ask them what they mean. Without a shared vocabulary, conversation is fruitless.

For 50-plus years, William F. Buckley Jr. gave speeches. After almost every speech, there was a Q&A, and the most frequently asked question, by far, was, “What is conservatism? Can you give us a definition?”

WFB had a hard time with that, which may seem surprising. He was widely regarded as the founder of the modern American conservative movement, and he was the most articulate of men.

But he had a hard time answering because conservatism is not a doctrine, a program, or an ideology. It is more like a cast of mind, an outlook, a way of being.

In 2019, another leading conservative, George F. Will, published his summa, giving it the title “The Conservative Sensibility.”

I myself have a very long speech on what conservatism is. I will spare you the speech but give you a few ideas, for your consideration.

There are two major senses of conservatism—one depends on time and place, the other does not.

“What do you want to conserve?” That is a fundamental question. People want to conserve different things in different times and places.

In Europe, the conservative once favored throne and altar. (Some still do.) The conservative wanted to uphold heredity, station, hierarchy, and the like.

The American conservative has always been very different. By and large, we want to preserve the principles and ideals of the American founding—which come from the Enlightenment.

What are some of those principles and ideals? Well, sing along: limited government; the rule of law; constitutionalism; individual rights; separation of powers, including an independent judiciary; freedom of expression; freedom of worship, or non-worship…

I mentioned another sense of conservatism, one that does not depend on time and place. You’ve heard of a conservative driver, or a conservative dresser, or a conservative investor.

“Look before you leap.” “Err on the side of caution.” “When it’s not necessary to change, it’s necessary not to change.” And so on.

Back to the American founding, and what it represents. Our founding is an expression of liberalism, meaning classical liberalism. So, paradoxically, the American conservative is a defender of liberalism (classically understood).

In a conversation with me, Harvey C. Mansfield, the professor of government at Harvard, and an exemplary conservative, put it well:

I am not primarily conservative. I consider conservatism to be within liberalism, in the extended sense. And the extended sense comes from John Locke in the seventeenth century, and Adam Smith and David Hume in the eighteenth. Edmund Burke.

Mansfield was speaking about a society based on individual rights.

But there is another realm, apart from liberalism, apart from mere rights (if rights can ever be described as “mere”)—and that is “the land of virtue,” as Mansfield put it. In other words: You may have a right to do it (whatever “it” is). But is it right to do?

The foe of every liberal, whether he is right-leaning or left-leaning, is illiberalism. “Illiberalism lives on both the left and the right, at the extremes,” said Mansfield. The will to power, the lust for control, is perpetual, because it is human. It must always be guarded against, and tamped down, if possible.

In America today, there are many who belong to what they call the “New Right” or the “post-liberal Right.” They regard the founding as a colossal error.

Can you be a conservative and despise the founding? Yes—but not an American conservative, I would say.

The New Rightists admire many illiberal leaders around the world, not the least of them Viktor Orbán, in Hungary. Launching his fourth term in 2018 (he is now on his fifth), Orbán made an interesting statement: “We need to say it out loud because you can’t reform a nation in secrecy: The era of liberal democracy is over.”

Cheering in America for Orbán and his party was Patrick J. Buchanan, a godfather of our New Right. He wrote, “The democracy worshippers of the West cannot compete with the authoritarians in meeting the crisis of our time because they do not see what is happening to the West as a crisis.”

Leaving aside the phrase “democracy worshippers,” I appreciate the word “authoritarians,” for its candor.

Here is some more candor. Hungarians, Buchanan wrote, “have used democratic means to elect autocratic men who will put the Hungarian nation first.”

Many people have pointed out that America’s New Rightists don’t seem to like America all that much. Have some more Pat Buchanan, from that same column I have been quoting.

“To much of the world,” he wrote, “America has become the most secularized and decadent society on earth, and the title the Ayatollah bestowed upon us, ‘The Great Satan,’ is not altogether undeserved.”

Two and a half years before, Buchanan had said something that stood out to me. This was in October 2016, when Donald Trump, the Republican presidential nominee, was refusing to say whether he would accept the result of the election.

The “populist-nationalist Right,” said Buchanan, was “moving beyond the niceties of liberal democracy to save the America they love.”

One man’s niceties are another man’s preconditions for a decent national and political life.

Milton Friedman was certainly a liberal democrat, i.e., a champion of liberal democracy. He is often called a “libertarian.” Bill Buckley sometimes applied this designation to himself. A 1993 collection, he subtitled “Reflections of a Libertarian Journalist.”

In 1962, Friedman published his quickly classic Capitalism and Freedom. He dealt with the problem of words, or designations, in his introduction. “Because of the corruption of the term ‘liberalism,’” he wrote, “the views that formerly went under that name are now often labeled ‘conservatism.’” But to Friedman, that would not do.

He told the reader, or warned the reader, that he was going to stick with “liberalism.” He would use it “in its original sense—as the doctrines pertaining to a free man.”

Fast forward to 2023, when a biography was published. Its title? “Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative.”

Next year, Americans will celebrate the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. In 1926, for the 150th, a sterling conservative was president: Calvin Coolidge. On July 4, he said the following:

About the Declaration there is a finality that is exceedingly restful. It is often asserted that the world has made a great deal of progress since 1776, that we have had new thoughts and new experiences which have given us a great advance over the people of that day, and that we may therefore very well discard their conclusions for something more modern.

Coolidge then delivered a decisive blow:

But that reasoning cannot be applied to this great charter. If all men are created equal, that is final. If they are endowed with inalienable rights, that is final. If governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, that is final. No advance, no progress, can be made beyond these propositions.

Like you, perhaps, I have very strong views on politics and policy—economic policy, foreign policy, education policy, etc. Above those views, however, is the conviction that our liberal democracy, in republican form, is a great and good thing that must be conserved.

On the fence about becoming a paid subscriber? We have a special offer to make the decision easier for you: $49 for an annual subscription—a 30% discount—now through November 8. Paid subscribers get exclusive benefits like access to interactive Zoom calls with Garry Kasparov. Anyone who signs up as a premium subscriber by noon today (October 31) will be automatically entered to win a chess set signed by Garry Kasparov.

More from The Next Move:

‘Dead Woman Walking—and Talking’

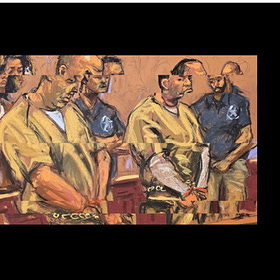

Two men hired to kill Masih Alinejad, the activist from Iran, are sentenced to prison.

Fortune Favors the Bold

Welcoming Jay Nordlinger to The Next Move as we build a bench of people defending freedom and democracy.

Were it possible to like this piece multiple times I would do so.

I am interested in your views on how the Claremont Institute and The Heritage Foundation can still claim to support the Founding and also support the largest expansion of presidential power in America history. I am ashamed to say that I worked for a time for both in the 80s and 90s when they supported the Constitution.