Yes, There’s Still A Shared American Identity

And here’s how we can make it a force for good.

By Colin Woodard

As a Russian-speaking half-Armenian, half-Jewish kid growing up in Soviet Azerbaijan, the complexity of nationhood and nationality was all around me. Every country inevitably faces an identity crisis, and it can feel especially fraught in a country like the United States: a multilingual, multiethnic, politically polarized democracy of over 350 million people.

At The Next Move, we don't just want to focus on our nation's divisions, though. Our purpose is to offer a positive vision for the nation's future. That's why Colin Woodard’s research and insight are key. A world-class intellectual, whose research has revealed the differences among Americans, his new project points us toward what we have in common.

Even though I’m not American, I’ve long believed in America as a shining city on a hill. Sharing this type of research can help Americans rediscover their common identity in spite of all the attempts to divide them.

I hope you find Colin’s work as insightful as I have—and, as always, please let us know what you think in the comments!

— Garry Kasparov

What makes an American? Countries with hundreds and even thousands of years of shared language and religion have struggled—even violently—to determine the contours of their own common identities. Americans lack even these basic contours of common national identity.

How we describe American nationhood is even more important today as ascendent extremists and demagogues put forth their own definitions to create rifts for political gain. If a positive identity exists as a contrast to divide-and-conquer tactics, we need to be able to confidently assert that alternative. This is the thrust of the work I’ve been leading for two years at Nationhood Lab, the research project I founded at Salve Regina University’s Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy. Our goal: to discover and develop a broadly held story of common national purpose.

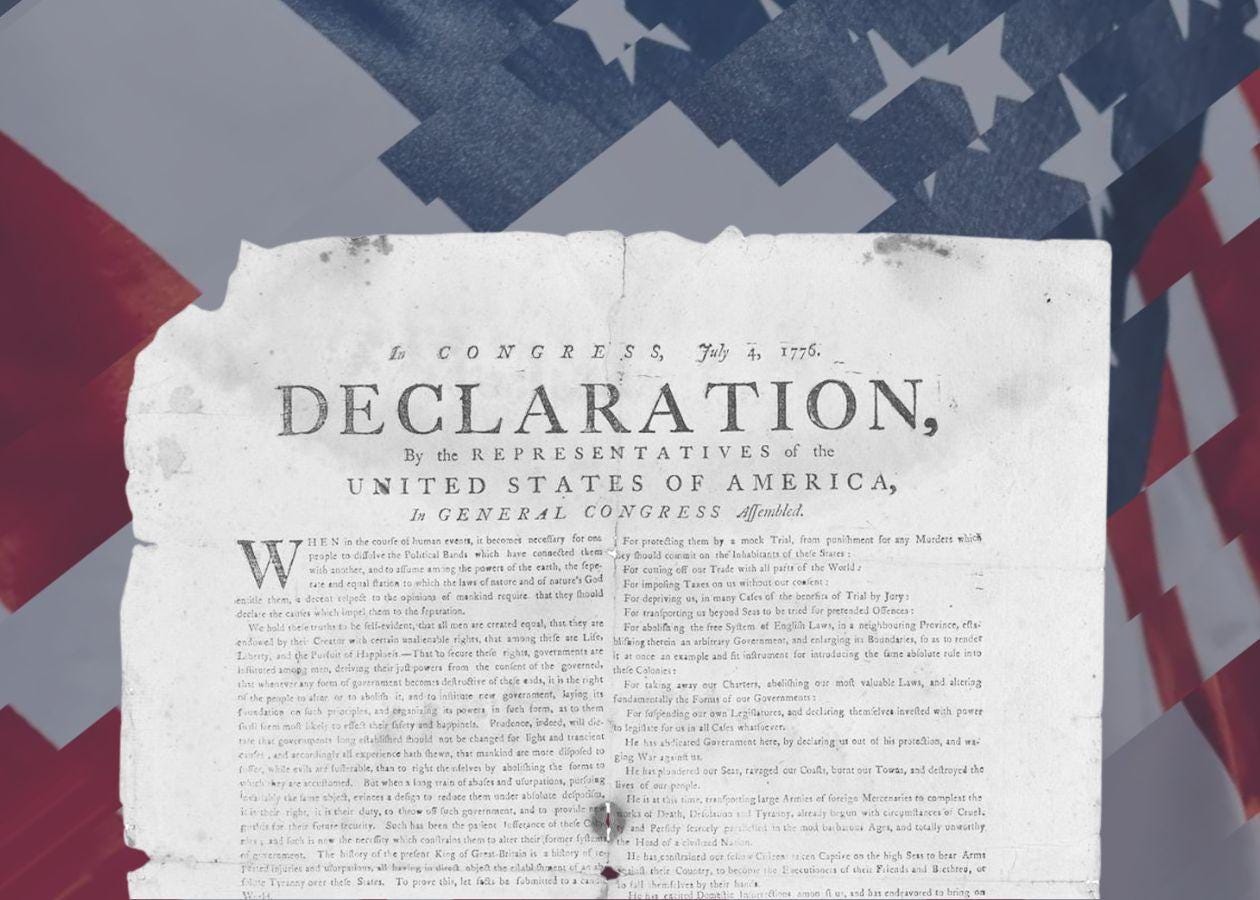

A big part of what we’ve found is that ours is not a typical country. We found that Americans share a broad consensus that the purpose of the United States is to seek to achieve the civic ideals set forth in the Declaration of Independence. America is a mission-driven organization and the Declaration of Independence is our mission statement. It argues that people have a natural, God-given right to be free from tyranny, to choose our leaders, and to pursue happiness. Most importantly, it asserts that we as Americans are in it together and have a responsibility to protect one another’s liberties.

To be American, according to this definition of the United States, is to be committed to these beliefs about the nature of the people and the universe. And these ideals are far more widely held, our research revealed, than our present political polarization might suggest.

According to our preliminary national baseline poll, 63 percent of Americans believe we are united “not by a shared religion or ancestry or history, but by our shared commitment to a set of American founding ideals: that we all have inherent and equal rights to live, to not be tyrannized, and to pursue happiness as we each understand it.” Across almost every demographic, our fellow citizens consistently tell us that they prefer a definition of American identity undergirded by democratic ideals over those characterized by “national loyalty” or blood-and-soil nationalism.

Even more promising, Americans overwhelmingly stand by the emphasis on mutual responsibility for our neighbors found in the Declaration of Independence. In a poll of 2,700 Americans, respondents expressed support by a 97-2 margin for the idea that we are duty-bound to stand up for one another's rights.

We then worked to optimize our messaging and tested various alternative formulations of our prompts in additional polls and in qualitative interviews with dozens of representative Americans.

Here’s an excerpt from that final script:

We are, as Americans, in a covenant to defend one another’s natural rights...

to survive;

to live safe in their own person, free from domination;

to live the life they choose for themselves;

and to take part in determining who represents us and in holding them accountable.

That’s the American Promise, our mutual pledge to uphold these inalienable rights. And the American Experiment is the effort – despite the despotic track record of human history -- to build a nation, a society, a world where that is possible. We’re a people united by our commitment to uphold and defend this experiment, lest it perish from the Earth.

These are the ideals Frederick Douglass fought for in every speech he gave. This is Lincoln at Gettysburg and Martin Luther King Jr. on the Mall. They’re ideals we’ve spent 250 years struggling to achieve, ideals contested from the outset by those who would make our country something far less, just another nation-state built on blood—tribal kinship, inherited rule, inherited slavery or inherited servitude—where rights are things granted by superiors when they are granted at all.

Americans fought a Civil War over them at home and a World War for them abroad and advanced them at Seneca Falls, Selma and Stonewall. They’re ideals each generation must fight for and that we fight for today. We reckon with our shortcomings, take pride in our advances, and pledge ourselves to make our Union more perfect.

You don’t have to memorize this script verbatim. The point is in the broad strokes: that these are values the vast majority of Americans align on, a reference point that you can return to in order to judge politicians’ actions and persuade your fellow citizens.

That doesn’t mean that we as Americans are perfectly aligned on everything. The Nationhood Lab’s final prompt for survey-takers—a mini-speech on American national identity, if you will—has been tweaked and refined as we try to maximize the appeal of a shared American identity across partisan lines and other dividers. Even while we tried to capture as broad a segment of the electorate as possible, parts of this statement still rankle some Americans.

Some of these concerns were aesthetic—conservatives tend to gravitate toward terms like tyranny. But other disagreements were more substantive. Right-leaning respondents often bristle at a focus on our failures and internal struggles for self-improvement—the references to Seneca Falls, Selma, and Stonewall. They prefer recalling our triumphs over external enemies—at Valley Forge and Yorktown, in the trenches of France, and on the beaches of Normandy. Meanwhile, more progressive voters require references to our historic betrayals of the Declaration of Independence before they are comfortable re-embracing it.

So feel free to adjust based on whom you’re speaking with, but remember that these differences are marginal when judged against the broad acceptance of democratic rights and shared responsibility for our neighbors. What we need now is leadership to center the positive aspects of the American character.

Identity can be a force for good when it’s leveraged to build communities rather than erect fences.

Colin Woodard is the author of six books including Union: The Struggle to Forge the Story of United States Nationhood and American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. He is the director of Nationhood Lab at Salve Regina University’s Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy.

I think this is important research that should be messaged

let's meet in The Big Middle, where most Americans are, and come to consensus on solutions to our common problems