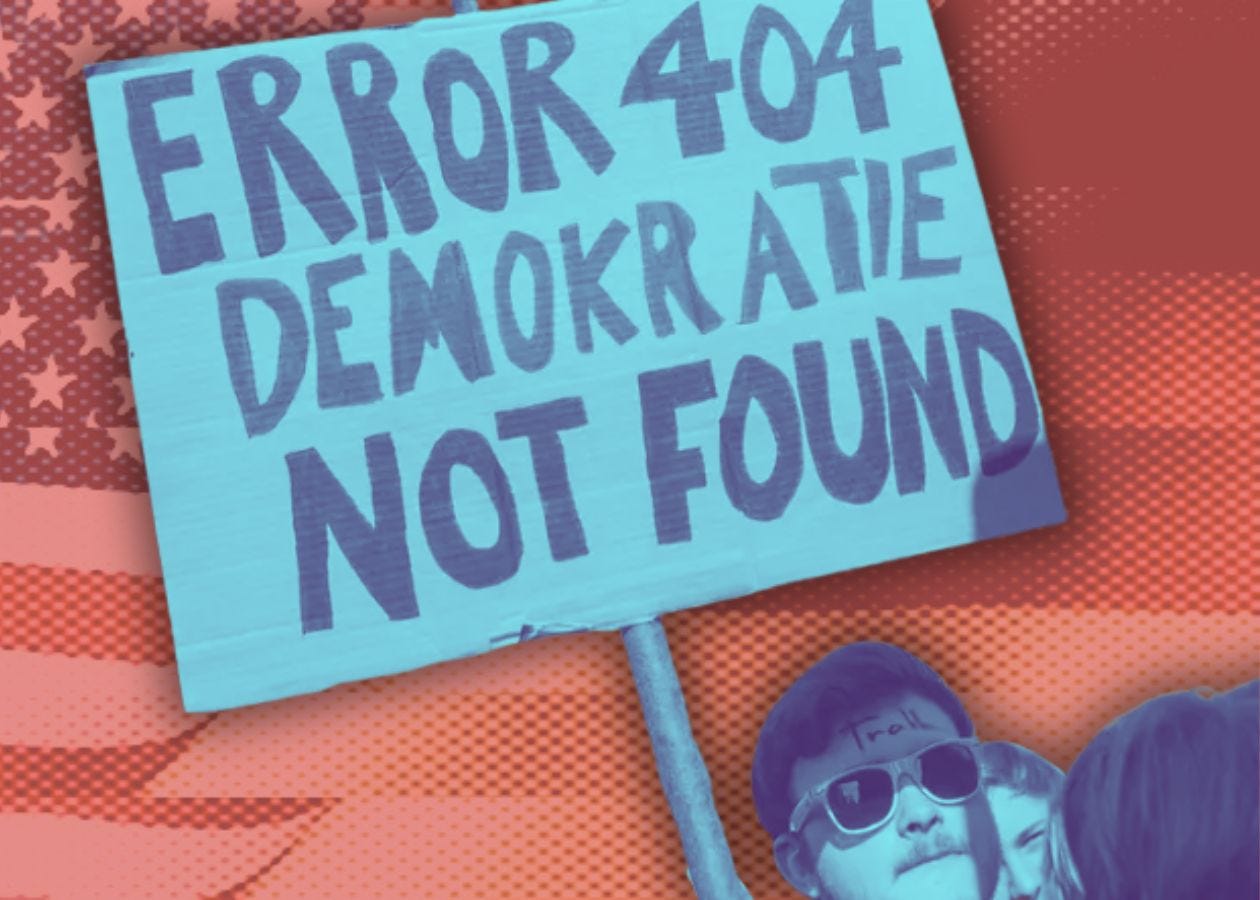

Why We Can’t Protect Democracy By Banning the Bad Guys.

The debate in Germany about banning the AfD focuses on a real threat: the far-right. But a party ban is not the appropriate solution in a liberal democracy.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This piece is part of a debate series that poses the question: Is it ever appropriate to ban extremist actors in a democracy? Is it overreach and political malpractice, or the proactive defense needed to stop authoritarianism before it destroys the system from the inside? Using the example of the far-right AfD party in Germany, this piece from leading German political commentator Heinrich Wefing, argues against a ban. Read his perspective, then read the opposing viewpoint from his colleague, Eva Ricarda Lautsch, and let us know what you think!

Heinrich Wefing is the head of the politics department at Die Zeit, one of Germany’s top newspapers. From 1996 to 2007, he was a feature editor at the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, working mostly in Berlin, and spending three years as a US West Coast correspondent in San Francisco. He has been with Die Zeit since 2008.

The tone is off, the volume is obviously overdriven, but the US secretary of state hits a sore spot. “This isn't democracy. It's tyranny in disguise,” Marco Rubio wrote on Twitter after the German’s domestic intelligence service, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, or Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (BfV), formally classified the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), Germany's largest opposition party, as “proven right-wing extremist.” There is now a political debate as to whether to ban the party, dividing the governing coalition of the Christian Democratic Union (which is skeptical of a ban) and the Social Democratic Party (which, as of late June, is preparing for a ban).

The Federal Republic of Germany is far from a tyranny; the country is probably one of the most liberal states in the world, but there is something paradoxical in the concept of “defensive democracy,” which is part of post-war Germany’s DNA: The “right-wing extremist” label isn’t just a shorthand description but an official category that opens up a democratically elected party to monitoring by the BfV—or even a ban—if they are deemed to endanger democracy. These are authoritarian instruments for protecting freedom. They are anti-democratic means for defending democracy.

The framers of the 1949 German Constitution wanted it exactly this way. They witnessed how Hitler and the Nazis undermined the interwar Weimar Republic by abusing its own democratic institutions. Hitler did not come to power through a putsch, but through entirely legal means.

The Nazis were open about this from the outset. “We come not as friends, nor as neutrals. We come as enemies! As the wolf breaks into the flock of sheep, so we come,” Hitler's propaganda chief, Joseph Goebbels, declared in 1928 when the Nazis first entered parliament. The founders of the federal republic determined that infiltration of democratic organs should never be possible again.

“We have learnt from our history that rightwing extremism needs to be stopped,” wrote the German Foreign Office in a sharp reply to Rubio and a clear reference to the Nazis.

Allowing the secret service to monitor an elected party is certainly problematic. On principle, banning an elected party is an authoritarian measure: Voters are deprived of their representation, the party loses its opportunity to shape policy, and democracy is curtailed. Even in the shadow of World War II, the founders of the federal republic understood this. Therefore, the German constitution only provides for a party ban as a last resort, as a nuclear option.

Following the BfV's classification of the AfD as “proven right-wing extremist,” there is now heated debate in Germany about a possible ban on the party. It is one of the most consequential political decisions the country faces.

Make no mistake: The AfD is racist, xenophobic, and in some cases antisemitic. Nevertheless, it should not be banned. Not because that would be an act of tyranny, as Marco Rubio claims, but because there are compelling legal and political arguments against a ban. Let's start with the legal ones.

The decision to ban a party is not made by the executive or legislative branches—which would open up opportunities for politicized attacks—but by Germany's Federal Constitutional Court. The court in Karlsruhe has already banned parties twice in the 1950s, while in two other cases in 2003 and 2017 an attempted ban failed. In all four cases, the judges defined very strict criteria.

Simply spreading anti-constitutional ideas is not sufficient cause for a party to be banned; the Federal Constitutional Court is clear on this point. What's required is an “actively combative, aggressive stance” toward democracy, as the Karlsruhe judges put it; it must be proven that the party intends to abolish the liberal order of the Basic Law—with its fundamental pillars of human dignity, the rule of law, and democracy. And that means the entire party, not just individual loudmouths and agitators.

The AfD is problematic, yes. That the AfD has truly crossed the legally-demarcated threshold to be banned, that it can be proven beyond doubt–that is by no means certain. In its platforms and statements, the party explicitly declares its commitment to the constitution and democracy. Of course, one could argue that this is all just ornamentation, lies, and deception. But then one would have to prove it. The new report from the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution doesn’t meet that standard.

And should a party ban be attempted in Karlsruhe only to fail, should the Constitutional Court certify that the AfD may be extreme, but not unconstitutional—then this entire exercise will end up being a disaster for the centrist parties.

This brings us to the political case against a ban. First, quite practically: A party ban procedure at the Federal Constitutional Court takes a long time: at least two years, more likely four or five. The court reviews the situation thoroughly, hears experts and representatives from all parties involved, and will not allow itself to be rushed.

During this period, the AfD will portray itself as a victim, cultivating its martyr status. With some justification, the AfD will accuse other parties of running out of ideas, of having given up politically, of not wanting to defend democracy at all, but merely their own status.

Meanwhile, the AfD is likely to continue growing. In next year's state elections in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Saxony-Anhalt, it could become the largest party. If the AfD wins the race for state premier—the German equivalent of an American governor—then a ban would lead to the seniormost state-level official being removed from office. The AfD seats would not be filled, which could determine which bloc has a majority in parliament. This all presents a risk of considerable escalation.

Sure, one might hope ban proceedings in Karlsruhe might deter voters from voting for the AfD. That was also the hope as the AfD’s classification by the authorities evolved: first, when the AfD was initially labeled under suspicion of right-wing extremism, then, in parts, as confirmed right-wing extremist, and so on. The effect was always the same: the AfD didn't lose votes, it gained them. Its supporters know what kind of party the AfD is, which is precisely why they like it.

The most probable outcome is an opposite-deterrant effect: While underway, a party ban procedure threatens to exacerbate the polarization it is intended to combat.

And finally, perhaps the most important argument against a ban: Even if the AfD were banned, if it lost all its seats and its assets—the thoughts, beliefs, and anger of its voters would not disappear. They would seek other vehicles, other leaders, and many of the AfD's supporters might even become further radicalized.

Does that necessarily have to be the case? Probably not. After 1945, there were suddenly no more Nazis in Germany; no one could remember being enthusiastic about the Nazi Party; a nation of party loyalists conveniently became a nation of resistance fighters. But that was after six years of war, total military defeat, and the Holocaust.

Today, the historical situation is different. We live in a time when liberal democracy is in recession and right-wing populists and authoritarians are on the rise everywhere. This is a secular trend, a global vibe shift that doesn't end at national borders and probably doesn't halt for legal stop signs either.

Take France as an example: A court’s decision to suspend Marine Le Pen’s right to stand for election for five years has not harmed her party, the National Rally. According to current polls, her replacement, Jordan Bardella, would almost certainly make it to the runoff in the next French presidential election. In America, attempts to impeach Donald Trump, try him for various crimes, and even remove him from the ballot only fed his popularity and helped return him to the White House.

The most recent example is Romania. In December 2024, the Constitutional Court in Bucharest annulled the election of the far-right and pro-Russian presidential candidate Calin Georgescu due to alleged Kremlin interference and ordered a new round of voting. Another far-right candidate then ran in the repeat election, only narrowly missing victory in the runoff.

In other words: large sections of the population cannot be excluded from democratic processes by decree. Relying on banning the AfD is a legal fantasy of exoneration. What belongs in parliaments, in council chambers, and even on the streets cannot be delegated to the courtrooms.