Jay Nordlinger is a senior resident fellow at the Renew Democracy Initiative and a contributor at The Next Move.

All of my life, I have burned at, and kicked against, the image of “the ugly American.” The phrase comes from the title of a 1958 novel by Eugene Burdick and William Lederer. It’s about US diplomats in Southeast Asia. It was made into a movie starring Marlon Brando.

What is, who is, the ugly American? The lout in the floral shirt, thinking that the locals will understand English better if only he yells.

In common with antisemitism, anti-Americanism is amazingly versatile. Writers such as David Pryce-Jones and Paul Hollander have noticed this.

To the antisemite, the Jew can be a capitalist or a socialist, depending on the need of the moment. He can be a top hat–wearing financier or a Bolshevik. He is clannish, not willing to integrate. On the other hand, he infiltrates everything.

And the American? He is insular, blinkered, unwilling to travel. Or, if you like, he is all too present, all over the world, despoiling every café and museum. He is the fat slob: the couch potato. He is also the body-worshipping health fanatic.

For many people, study abroad is formative. So it was for me, when I was in college. I experienced the anti-Americanism of many Europeans. More important, I experienced the anti-Americanism of many of my fellow Americans.

You’ve heard about the American kid who puts a Canadian maple leaf on his backpack. That stereotype is real. On a train from Luxembourg down to Florence, the young American sitting across from me said that she was hoping to pass for German.

German!

Some of the Americans simply didn’t want to be hassled. They wanted to be incognito. Others were ashamed of their country, especially of its role in the world. These were often called “self-hating Americans.” But I did not detect any self-hatred in them. On the contrary, they were self-loving. It was others they hated (e.g., Ronald Reagan).

I had always been a patriotic person—I thought the American founding was a great force for good in the world—but I emerged from my time abroad more patriotic than ever.

When was that time? Well, I was a student in Italy during the summer of 1984. That fall, there was a general election campaign at home. In October, Vice President Bush debated the Democratic nominee, Geraldine Ferraro. At one point, he said, “I’ll be honest with you: it’s a joy to serve with a president who does not apologize for the United States of America.” Ferraro reacted with a quizzical look.

I knew exactly what he meant, and I loved it.

Fast forward almost 20 years to 2003. Bush’s eldest son is president and his secretary of state is Colin Powell. I am present in Davos when George Carey, the former archbishop of Canterbury, asks a question of Powell. The gist of it is: Is not the United States today overly reliant on “hard power” rather than “soft power”?

Powell says that the US deploys “soft power” in myriad ways, and very effectively. But “hard power” is often necessary, he says, adding this:

We have gone forth from our shores repeatedly over the last 100 years—and we’ve done this as recently as the last year in Afghanistan—and put wonderful young men and women at risk, many of whom have lost their lives, and we have asked for nothing except enough ground to bury them in.

I thought that was just right.

The next year saw another general election: President Bush vs. John Kerry. In a debate, Kerry spoke of “the global test”—a test that US policy ought to pass. Does the world approve (or at least accept) or not?

“Nonsense,” said the likes of me. “American policies ought to be in the American interest. And our interest, more often than not, coincides with the interest of mankind at large.”

I could go on—and have, in countless articles, plus books—but have I established my bona fides? My credentials as an America-defending, flag-waving conservative?

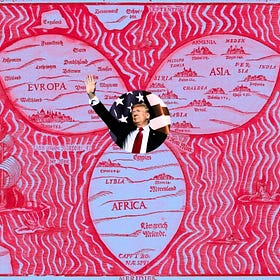

Chances are, you knew where this was heading—to Donald Trump. He has made “the ugly American” real. And he is not a random tourist; he is the president of the United States, the embodiment of America to millions, or billions.

In his first term—May 2017—there was a small incident, but telling. Leaders at a NATO summit in Brussels were assembling for something like a group photo. Trump shoved one of them, Duško Marković, the prime minister of Montenegro, out of the way, to get to the center.

A video of this incident “went viral,” globally.

Montenegro is a teeny-tiny country, powerless. The US is something very different. Can’t the American president afford to be gracious?

More recently, Trump has been threatening a NATO ally, Denmark, over Greenland. Last week, he said, “We’re going to be doing something with Greenland, either the nice way or the more difficult way.” That is the talk of a mafia boss.

Asked whether there were constraints on his global powers, Trump said, “Yeah, there is one thing. My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me. I don’t need international law.”

In the early 2000s, many people charged that the United States was waging what we then called the War on Terror for one reason: oil. “No blood for oil!” went the cry. And what has Trump said about Venezuela? “We’re going to be taking oil.” “We’re going to keep the oil.”

He circulated a meme that labeled him—that designated him—the “acting president of Venezuela.”

Last April, I traveled to Denmark to speak to people about the suddenly, dramatically altered relations between Washington and Copenhagen. The people I spoke with were not only indignant, outraged, or appalled. They were “heartbroken,” as at least two of them said.

(For my report from Denmark, go here.)

I’m not talking about Euro-lefties (who would not be at all heartbroken). I’m not talking about Marxists or hippies wearing Che Guevara T-shirts. (Guevara was everywhere when I was a student in Europe, along with Marilyn Monroe and Elvis).

No, these are conservatives and Atlanticists who loved Reagan and have always defended America and our role in the world, especially Europe.

What Lincoln said of Clay, in his eulogy, can be said of many of us:

He loved his country partly because it was his own country, but mostly because it was a free country; and he burned with a zeal for its advancement, prosperity, and glory because he saw in such the advancement, prosperity, and glory of human liberty ...

Another statement is attributed to Tocqueville: “America is great because she is good.” The great Frenchman did not say or write those words, as far as can be determined, but they are worthy nonetheless.

And it’s up to each of us, as citizens, to express America the Beautiful, not America the Ugly.

Jay-Your “little essay” is a gem. More would likely have been too much more. More people, especially those with me on the “left”, need to feel this way.

"The Ugly American" has been wilfully mistaken for a training manual by the very subjects of its ridicule. They've also done the same with Orwell's "1984".